Background Information

In post-WWII society, the two biggest deterrents are nuclear weapons and diplomacy. However, in recent history, we have begun to see a third, novel form of deterrence: economic co-dependence. This transformation of the geopolitical landscape is best exemplified by Taiwan, a country 0.37% the size of the United States and 1.6% of China’s population, still managing to produce 92% of the world’s high-end semiconductor chips. Taiwan’s complete dominance of the semiconductor industry despite its small size is nothing short of extraordinary, beating out both China and the US, the top economies in the world, with near-infinite amounts of land, population, and resources to devote to semiconductor research and manufacturing. This miracle’s progenitor is no fairy, however, and instead takes the form of a Taiwanese-American entrepreneur and engineer by the name of Morris Chang. From humble beginnings in Hong Kong, he immigrated to the United States to pursue electrical engineering at MIT and eventually found himself working at Texas Instruments. While certainly impressive, this trajectory is not particularly unheard of. What really set Morris apart from other electrical engineers was his discovery of a revolutionary principle behind how chip manufacturing supply chains work. Previously, most chip design companies had to purchase their own FAB, which stands for semiproductor fabrication plant, which wasted critical money and time that could have instead been allocated for design and testing. His revolutionary idea was to diverge from vertical integration, which was so common in the chip industry, and pursue horizontal integration by creating a dedicated, non-affiliated FAB in Taiwan. This way, companies can save on the extensive labor and R&D costs associated with running a FAB and instead outsource the manufacturing of the chips to companies like TSMC and other companies born from Morris’s gambit. The ability to provide a cheap and efficient alternative to vertically integrated FABS makes companies flock to TSMC and almost abandon local US and Chinese FABS altogether. This has created a pseudo-monopoly over chip creation for the Taiwanese government, which helps Taiwan gain leverage in the geopolitical sphere. Because of both the US’s and China’s reliance on their chips, it is paramount that Taiwanese FABS remain functional. This has become especially important in recent years, as China’s President Xi Jinping has sworn to commit to the “reunification” of Taiwan with mainland China under the CCP. However, the Taiwanese government is not particularly enthusiastic about this idea. Tsai Ing-wen, the current president, is a fervent advocate for political independence from the CCP, and her party, the DPP, is gaining significant political sway over the people of Taiwan, with a recent study citing that over 70% of Taiwanese citizens consider themselves to be Taiwanese rather than Chinese and want political independence. The stark difference between the actions of the Taiwanese government and the desires of the CCP would normally have led to their reoccupation, yet Xi likely remains reluctant due to the economic codependence between the nations. Because the majority of the modern chips that are critical to the Chinese infrastructure are manufactured in Taiwan, a full-out invasion could lead to the destruction of these crucial FABS and thereby debilitate the Chinese. These chip FABS, like TSMC, serve as a dome of protection against the unwelcome advances of the world’s superpowers, leading to economists coining it the “Silicon Shield,” which plays a major part in Taiwan’s defense strategy. However, this advantage only holds for as long as the Taiwanese hold their monopoly over the semiconductor industry. Both China and the US are beginning to manufacture their own chips, with China just recently implementing a fully operational 7nm FAB and the US stating that they will construct a 5 and 3 nm FAB in the near future. Although trailing behind the cutting-edge of established Taiwanese FABs, these pursuits depict China and the US’s conviction to narrow the gap, calling Taiwanese sovereignty into question as their defense against Chinese aggression is under pressure.

Implications

The recent U.S. tariffs and bans on exporting semiconductors to China expose a worrying new trend: after massive leaps and bounds in trade globalization in the 20th century, nations have begun to scale back and consolidate their supply chains, opting to rely on domestic industries rather than international cooperation. Conflicts between the U.S. and China, particularly over Taiwanese sovereignty, are centerstage in deglobalization, both through the breakdown of trade and cooperation between the two nations as well as the massive efforts in both nations to jumpstart a domestic semiconductor manufacturing industry. In fact, just last year, the United States Congress proposed the CHIPS Act, which directly allocated 280 billion dollars to domestic chip R&D and local manufacturing as well as pledged to further allocate funds if necessary. However, this sudden growing interest in semiconductors was not catalyzed by selfless desires to further an interesting field of science; rather, this massive investment came about largely due to the growing tensions between the US and its twin superpower China, specifically within the realm of armament. A recent example of this is the J-20, China’s first 5th generation fighterplane, which, aside from showing a dubious resemblance to the American F-35 and F-22 models, which were released a few years prior, also shared the name of top-of-the-line silicon chips with the Americans, which the US government sees as jeopardizing their military hegemony.

The CHIPS Act, while not directly inflammatory, represented an ultimatum to regain American decisive military and technological superiority as well as furthering the precedent of achieving economic independence from China. Starting in 2018 with the Trump administration, the US levied tariffs against China for its perceived unfair trade policies regarding how intellectual property rights are protected, namely how all US companies must divulge their technology to a local Chinese company in order to operate. In retaliation, the Chinese raised their own tariffs and began a mutual trade war, which is still ongoing. This economic feud between giants represents a divergence from the previous decade of globalization, which was paramount to the economic growth of post-Cold War isolationism.

These antagonisms harm both countries because their economies are built on each other.

China is a primarily brute-force industrial manufacturing country, while the US is more prominent in design and innovation. As mentioned before, semiconductors are crucial in the military, and the US, wary of the burgeoning competition from China in the semiconductor industry, views such initiatives as defensive measures to maintain its technological hegemony. The establishment of Intel’s 5nm fab can be seen as a proactive step in safeguarding American interests amidst growing Chinese prowess in advanced manufacturing.

Game Theory Application

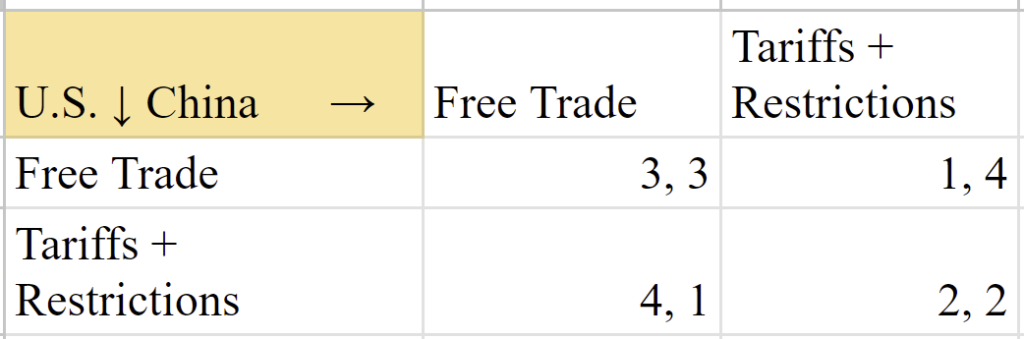

Typically, tariffs and hindrances to free trade are looked down upon, especially by economists. Not only do they tend to impede economic efficiency by halting the gains from comparative advantage from trade between countries, but they also hurt everybody, including domestic producers. However, arguably the greatest benefit of free trade is that it fosters interdependence among countries, thereby reducing the likelihood of conflict. As French economist Frédéric Bastiat declared, “When goods do not cross borders, soldiers will.” Therefore, if this is true, the scenario for the U.S. as player one and China as player two will be similar to the prisoner’s dilemma:

This sets the Nash equilibrium, with both countries implementing protectionist policies despite their best option being mutual cooperation. In the real world, this is indeed what happened with China responding to U.S. tariffs with retaliatory tariffs. However, the optimal solution, as modeled, will be allowing free trade between both countries. In that case, both countries may want to enact tariffs against each other to generate revenue or protect industries.

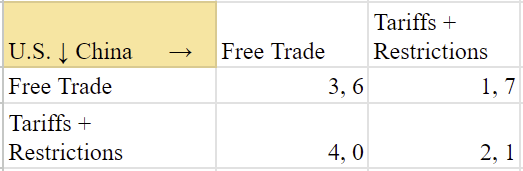

However, in this relationship, the U.S. maintains a hegemony over China in their semiconductor-producing capability. This implies that the tariffs would inflict more damage on China than the U.S., as China’s retaliatory tariffs would have less of an impact. Therefore, we can modify our game matrix as follows:

In this scenario, the Nash equilibrium is still to adopt protectionist policies; however, for China, the losses are aggravated. In the free trade scenario, China is delighted to get cheap semiconductors from the U.S. and benefit more than the U.S. would. On the contrary, China would be hurt a lot from tariffs since they do not yet have the capabilities to manufacture top-end semiconductors. Furthermore, it is unlikely that China would first implement trade restrictions since they are more dependent on U.S. action. It is also important to note the historically strained relationship between the two countries, and if the U.S. chooses to break their trust by implementing tariffs, China might never be willing to cooperate with the U.S. again, even if such a stance seems irrational in the long run. To make sure they are not too dependent on the U.S. for important semiconductors, China has recently been investing heavily in subsidizing its domestic semiconductor manufacturers in R&D, infrastructure development, human capital development, and strengthening intellectual property laws.

Bibliography

Bhatia, Sanuj. “Chip Nanometer Technology Explained, and Why the Smaller the Better.” Pocketnow, April 18, 2022. https://pocketnow.com/chip-nanometer-technology-explained/.

Brar, Aadil. 2023. “Would Taiwan’s Public Take up Arms in a War With China?” Newsweek, November 6, 2023. https://www.newsweek.com/taiwan-china-threat-defense-military-training-war-1841024.

“Country Comparison: China / Taiwan.” Worlddata.Info, www.worlddata.info/country-comparison.php?country1=CHN&country2=TWN. Accessed 17 Apr. 2024.

“Did Bastiat Say.” Online Library of Liberty. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/did-bastiat-say-when-goods-don-t-cross-borders-soldiers-will.

Ebrahimi, Arrian. “China Boosts Semiconductor Subsidies as US Tightens Restrictions.” – The Diplomat, September 28, 2023. https://thediplomat.com/2023/09/china-boosts-semiconductor-subsidies-as-us-tightens-restrictions/.

FLYING Magazine. 2021. “50 Years of Chinese Aviation Knockoffs.” November 10, 2021. https://www.flyingmag.com/photo-gallery-photos-50-years-chinese-aviation-knockoffs/.

Forbes Magazine. (n.d.). Morris Chang. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/profile/morris-chang/?sh=2ba507695fc4

House, White. 2023. “FACT SHEET: CHIPS and Science Act Will Lower Costs, Create Jobs, Strengthen Supply Chains, and Counter China.” The White House. February 3, 2023. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/09/fact-sheet-chips-and-science-act-will-lower-costs-create-jobs-strengthen-supply-chains-and-counter-china/.

Lüdtke, Lisa. 2023. “Will Taiwan’s Silicon Shield Protect It From China?” GIS Reports, July 24, 2023. https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/china-taiwan-silicon-shield/.

Pettinger, Tejvan. “Benefits of Free Trade.” Economics Help, March 28, 2020. https://www.economicshelp.org/trade2/benefits_free_trade/.

Shivakumar, Sujai, and Charles Wessner. “Semiconductors and National Defense: What Are the Stakes?” CSIS. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://www.csis.org/analysis/semiconductors-and-national-defense-what-are-stakes.

Siripurapu, Anshu. 2023. “The Contentious U.S.-China Trade Relationship.” Council on Foreign Relations, September 26, 2023. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/contentious-us-china-trade-relationship.