Today, $12.2 trillion in wealth is controlled by an estimated 2,640 billionaires, of which just under three quarters are self-made. Banning billionaires is a complicated proposition that could take on various forms depending on interpretation. For the purposes of this essay, banning billionaires refers to a government taxing them out of existence — taxation to the point that they lose their billionaire status altogether. How countries choose to implement and enforce such a policy, however, would be a decision beyond the scope of this essay. Instead, this essay will examine the economic consequences as a result of banning billionaires.

Proponents of removing billionaires, such as American senator Bernie Sanders who says that “[t]he US government should confiscate 100% of any money that Americans make above $999m,” believe that such a ban would reduce domestic wealth inequality. Member of Parliament for Islington North and former UK Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn expresses a similar view, and in a tweet writes that “in a fair society there would be no billionaires and no one would live in poverty.” While it seems reasonable that billionaires should be banned because they exacerbate the wealth gap, this logic is flawed. It does not account for the fact that real wages and the standard of living for the poorest decile has drastically improved over the last century, in large part due to the existence of billionaires. Goods that were once unattainable for the rich have now become basic necessities for the masses. The line of thought expressed by Sanders and Corbyn, among others, incorrectly treats the economy as a zero-sum game, wherein a billionaire’s increase in wealth equates to millions getting poorer. It is more reasonable to assume that the economy is a positive-sum game, where a billionaire’s innovations positively impact real gross domestic product (GDP), warranting their increase in wealth while concurrently raising the standard of living for the rest of the population. Take, for instance, China, which in 1981 had no billionaires and a poverty rate of 88.3%. Today, thanks in large part to the economic reforms of Deng Xiaoping, there are 395 Chinese billionaires and more than 800 million have been lifted out of poverty. The rich do not grow rich at the expense of the poor.

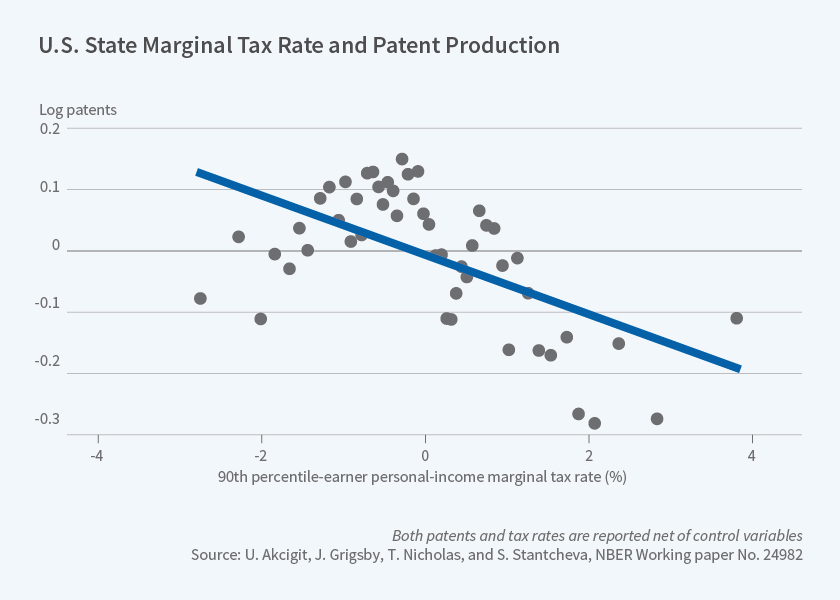

At first glance, banning billionaires by levying steep progressive taxes against them appears to be an effective method through which governments can raise capital. However, this line of reasoning overlooks the fact that an increase in tax rates for the ultra-rich decreases their opportunity cost of leisure. As tax rates increase, the cost of working starts to exceed its benefits. This leads to a variety of problems for governments, the most notable being dampened innovation. One way to quantitatively analyze innovation in a given economy is by examining patent production, which empirical evidence has suggested is negatively correlated to changes in the personal-income marginal tax rate, as noted in the figure above. As the ultra-rich lose incentive to work, a country’s innovation and real GDP growth slows — something that any government would rather avoid. Additionally, any benefits reaped by the government in the form of tax revenue would be quickly overshadowed by the costs incurred by levering such a high tax rate against the wealthy, as in the long run, the ultra-rich would no longer have a monetary incentive to productively contribute to the domestic economy. But upon closer examination, banning billionaires has even more of a pernicious effect on governments. Not only would countries have to reckon with a loss in overall domestic productivity, they would be faced with unprecedented capital flight as billionaires look to other countries for maintaining and growing their wealth. In this regard, banning billionaires can be framed as a collective action problem. Instead of raising the living standards of its poorest citizens, a ban on the ultra-rich would promote the outflow of billions of dollars, reducing domestic investment while simultaneously cutting the number of domestic jobs, increasing unemployment. In effect, a government banning billionaires would ultimately achieve the opposite of what was originally intended — it would cause the poor to grow poorer.

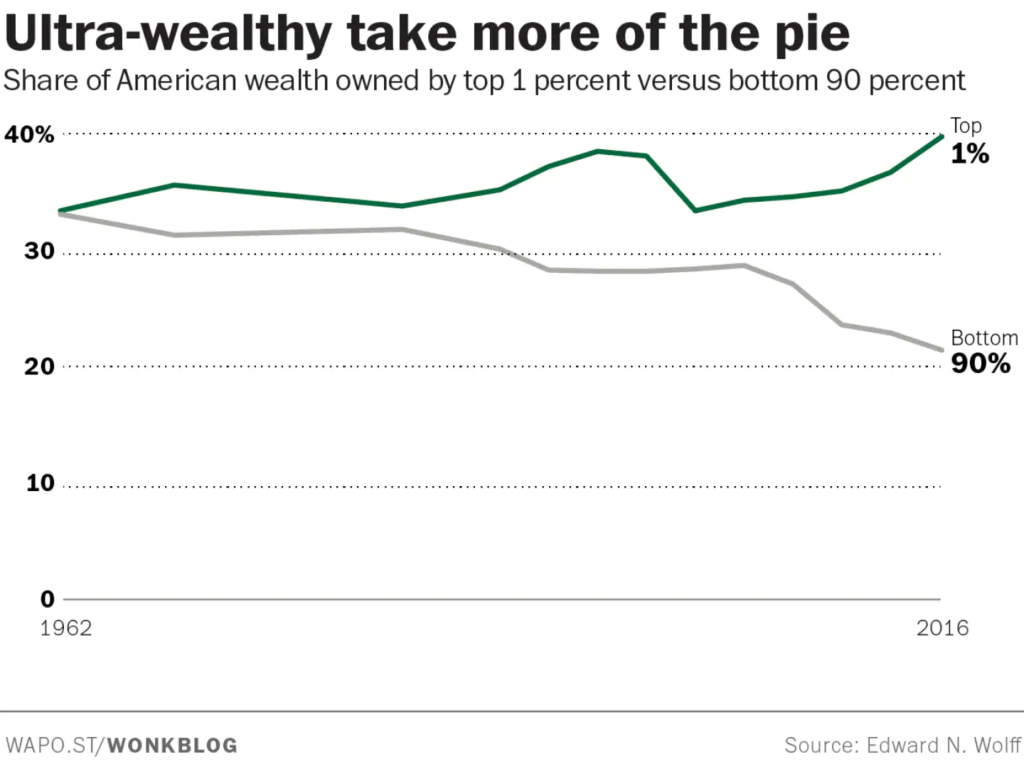

Proponents of banning billionaires would also have to contend with an overall loss in technological advancement. A large portion of the world’s billionaires are dubbed serial entrepreneurs — that is to say, they are able to repeatedly turn ideas into successful businesses that positively impact domestic economy through developments in technological capability. There are many relevant historical examples of entrepreneurs that continue to positively affect domestic economy even after gaining the title of billionaire. A ban would cut out all extrinsic motivation for billionaire serial entrepreneurs to pursue new projects — and the policy would make it irrational for billionaires to take on large risks by investing in capital-intensive projects that have yet to yield significant results. After all, why would one risk hundreds of millions of their own money if they have very limited upside and a large potential downside? Sure, it can be argued that technological innovation marches ahead regardless of whether or not billionaires take large risks by investing in experimental and capital-intensive projects. However, as noted by the aforementioned inverse correlation between patent production and tax rate, there is little doubt that progress is achieved more quickly with the financial backing provided by the ultra-rich. Still, even with the large contributions to society that billionaires make by taking on risk, the issue of wealth inequality remains.Ultimately, the crux of the issue yields itself to a simple cost-benefit analysis — whether or not billionaires benefit society enough to justify their extreme wealth. It is commonly thought that the economy is a zero-sum game wherein one person’s victory is indicative of another person’s loss. We believe that this is not the case — over time, the standard of living has continually increased. Real wealth accumulated by an individual does not necessarily detract from the wealth of others. This consideration that the economy is a positive-sum game is too frequently overlooked in traditional media. An increasingly large number of headlines reference the idea of wealth share without recognizing that total wealth continues to scale with technological advancement. Skeptical? Let’s take this graph originally published in the Washington Post.

It shows that the share of American wealth held by the bottom 90% has decreased from approximately one third in 1962 to just over one fifth in 2016 — a roughly 36% decrease. At first glance, this trend seems bleak. However, this graph leads the reader to incorrectly assume that the size of the pie is unchanging — in other words, it presents total American wealth since 1962 as static. One of the main measures of total domestic wealth is real GDP. Between 1962 and 2016, real GDP in America has grown to 17.57 trillion dollars, representing a more-than-fourfold increase since 1962. Notably, one third of one pie dwarfs in comparison to one fifth of five pies — so while it’s true that the wealth share of the bottom 90% has decreased since 1962, their total wealth has seen a more-than-twofold increase. All the while, US population has grown only 73.1%. Such an increase in wealth per capita is mirrored in the United Kingdom and across the globe, where the bottom 90% have witnessed tremendous economic growth since 1962. While billionaires capture a large portion of newly-generated wealth and have seen their wealth share increase in recent years — they also take on more risk in the form of capital-intensive projects —, the standard of living has continually increased for the vast majority. Innovations by billionaires positively impact more people than just the wealthy. Since 1952, the price of air conditioning in real terms has fallen ninety-seven percent — a prime example of how the technological advancements brought forth by the wealthy benefit more than just the wealthy themselves. More and more, once-luxury goods are becoming basic human necessities, and the endeavors of billionaires are able to continually impact society for the better. In banning billionaires, economic progress would slump and the standard of living would deteriorate universally; the economy is not zero-sum.

Unfortunately, there are billionaires who do not positively impact society. They inherit their wealth and corrupt government officials by passing bribes, exacerbate the growing issue of climate change, and negatively impact the rest of the population when evading taxes. How much of a burden to society are these billionaires? Do the costs of these “bad apple” billionaires exceed the benefits reaped from the others?

Political donations have long been central to a successful campaign, in the United States, the United Kingdom, and in democracies across the globe. Billionaires wield more influence over elections as a result of their large political donations. Often, it leads to one party controlling more funds than another; for example, between January and March of this year (2023), the conservative party in Britain received £6.4 million more in funding than the liberal party due to a £5 million donation by billionaire Mohamed Mansour. This unequal distribution of funds exemplifies the sway that the ultra-rich have on political campaigns, undermining the whole concept of a democracy. However, a ban on billionaires would not likely reduce the inequity already present in the democratic voting system by much. A study conducted in 2020 showed that roughly one fifth of US political giving is from corporations and executives, not primarily from billionaires. While a ban on billionaires would reduce the power that the ultra-rich yield, elections would still have intrinsic unfairness as a result of large corporate donations that, as some say, fail to accurately reflect the will of the people.

Another one of the largest issues that this generation will grapple with is climate change. One of the largest goals of the UN’s COP27 is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions such that irreversible anthropogenic damage to the climate is averted. It is estimated that the richest billionaires and their respective investments each emit an average of one million times more greenhouse gas than a typical person. As astounding as that figure sounds, it is important to recognize that for years there have been purported threats to the wellbeing of humanity — threats that have been solved with human ingenuity and technological innovation. Paul Ehrlich, professor emeritus of biology at Stanford University, expressed his concerns about overpopulation in his 1968 work, The Population Bomb, in which he claims that “the battle to feed humanity is already lost” and that “there will be famines.” His stark forecast has yet to come to fruition, in large part due to the rapid technological advancements in agriculture — for instance, vertical farming, improved fertilizer production, and genetic engineering, all of which are backed financially by billionaires. Even today, many new technologies aimed at drastically reducing climate disruption are funded by billionaires, such as investment in novel eco-friendly power generation, carbon capture, and greener concrete. Humanity will continue to face obstacles, but banning billionaires and grinding economic growth to a halt are no way to address the climate change issue. Solutions to the climate crisis will be found thanks to the financial backing of the ultra-wealthy — and instead of stopping at the hurdles to come, humanity will find itself pole vaulting over them. To ban billionaires would be a logistical challenge in itself, as many derive their wealth from the illiquid assets that they hold. Regardless, the net social benefit derived from the extremely wealthy greatly exceeds the situation wherein no one is rich and humans instead face the same “universal squalor.” The removal of billionaires would harm technological progress and economic growth. Serial entrepreneurship would be severely disincentivized. Though it would reduce relative wealth inequality, the slowed economic progress would lower the quality of life for all. While a ban could slash the carbon emissions of the ultra-rich, it would reduce the ease of capital acquisition and increase the cost of borrowing for climate-focused organizations. For the reasons elaborated upon above, banning billionaires is not a viable solution and would likely cause more harm than good. As a whole, billionaires are essential to the wellbeing of the global economy and continue to raise quality of life universally.

Bibliography

Agnew, Harriet, and Lucy Fisher. “Egypt-Born Billionaire Mohamed Mansour Tops UK Political Donations.” Financial Times, June 8, 2023. https://www.ft.com/content/fd7df5c0-9d13-4fff-be49-cf1404b02717.

Akcigit, Utuk, and Stefanie Stantcheva. “Taxation and Innovation.” NBER, September 2018. https://www.nber.org/reporter/2018number3/taxation-and-innovation.

Archie, Ayana. “Investments of 125 Billionaires Have the Same Carbon Footprint as France, Study Finds.” NPR, November 9, 2022. https://www.npr.org/2022/11/09/1135446721/billionaires-carbon-dioxide-emissions#:~:text=Some%20of%20the%20world’s%20richest,according%20to%20a%20new%20study.

Carnegie, Andrew. The “Gospel of Wealth”: Essays and Other Writings. Penguin Publishing Group, 2006.

Corbyn, Jeremy. “There Are 150 Billionaires in the UK While 14 Million People Live in Poverty. in a Fair Society There Would Be No Billionaires and No One Would Live in Poverty.” Twitter, November 1, 2019. https://twitter.com/jeremycorbyn/status/1190186804785418242?lang=en.

Costa, Nicolas. “The Economics of Billionaires.” Michigan Journal of Economics, April 14, 2021. https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/mje/2020/11/17/the-economics-of-billionaires/.

Ehrlich, Paul R. The Population Bomb. New York, NY: Ballantine Books, 1968.

Hammond, Alexander C.R., and Gale Pooley. “Air-Conditioning Costs Fell by 97 Percent since the 1950s.” Foundation for Economic Education, August 12, 2019. https://fee.org/articles/air-conditioning-costs-fell-by-97-percent-since-the-1950s/.

Ingraham, Christopher. “Analysis | the Richest 1 Percent Now Owns More of the Country’s Wealth than at Any Time in the Past 50 Years.” The Washington Post, November 24, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/12/06/the-richest-1-percent-now-owns-more-of-the-countrys-wealth-than-at-any-time-in-the-past-50-years/.

Investopedia. “How Much Would Steve Jobs Be Worth Today?” Forbes, October 6, 2011. https://www.forbes.com/sites/investopedia/2011/10/06/how-much-would-steve-jobs-be-worth-today/?sh=6bc87a145c65.

Kim, Soo Rin. “Just 12 Megadonors Accounted for 7.5% of Political Giving over Past Decade, Says Report.” ABC News, April 20, 2021. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/12-megadonors-accounted-75-political-giving-past-decade/story?id=77189636.

Njuki, Eric. “A Look at Agricultural Productivity Growth in the United States, 1948-2017.” USDA, March 5, 2020. https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2020/03/05/look-agricultural-productivity-growth-united-states-1948-2017.

Oxfam. “A Billionaire Is Responsible for a Million Times More Greenhouse Gas Emissions than the Average Person.” Oxfam, November 6, 2022. https://www.oxfamamerica.org/press/press-releases/a-billionaire-emits-a-million-times-more-greenhouse-gases-than-the-average-person/.

Peterson-Withorn, Chase. “Forbes’ 37th Annual World’s Billionaires List: Facts and Figures 2023.” Forbes, June 1, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/chasewithorn/2023/04/04/forbes-37th-annual-worlds-billionaires-list-facts-and-figures-2023/?sh=7f5e04f177d7.

“Population, Total – United States.” World Bank Open Data. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=US.

Teso, Edoardo. “When Executives Donate to Politicians, How Much Are They Keeping Their Companies’ Interests in Mind?” Kellogg Insight, October 5, 2020. https://insight.kellogg.northwestern.edu/article/executives-campaign-donations.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. “Real Gross Domestic Product [GDPC1], Retrieved from FRED.” St. Louis Fed, May 25, 2023. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GDPC1.

University of Warwick. “Almost Half of UK Political Donations Come from Private Wealthy ‘Super-Donors’, New Research Finds.” Department of Economics, University of Warwick, November 23, 2022. https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/news/2022/11/almost_half_of_uk_political_donations_come_from_private_wealthy_super_donors_new_research_finds/.

Vargas, Ramon A. “’They Can Survive Just Fine’: Bernie Sanders Says Income over $1bn Should Be Taxed at 100%.” The Guardian, May 2, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/may/02/bernie-sanders-interview-chris-wallace-tax-rich.

World Inequality Lab. “Global Wealth Inequality: The Rise of Multimillionaires.” World Inequality Report 2022, April 14, 2022. https://wir2022.wid.world/chapter-4/.

Zitelmann, Rainer. “No, the Rich Don’t Get Rich at the Expense of the Poor.” Forbes, October 12, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/rainerzitelmann/2019/05/14/no-the-rich-didnt-get-rich-at-the-expense-of-the-poor/.